Written by Alexandra Freeman, Octopus.ac founder.

I always said that the hard bit of improving the publication (and hence incentive) system in research was not coming up with a better way to do it – after all, that’s quite a low bar – or even in building the infrastructure for that new system. It’s in helping people move to using it. And that’s where we are now with Octopus.

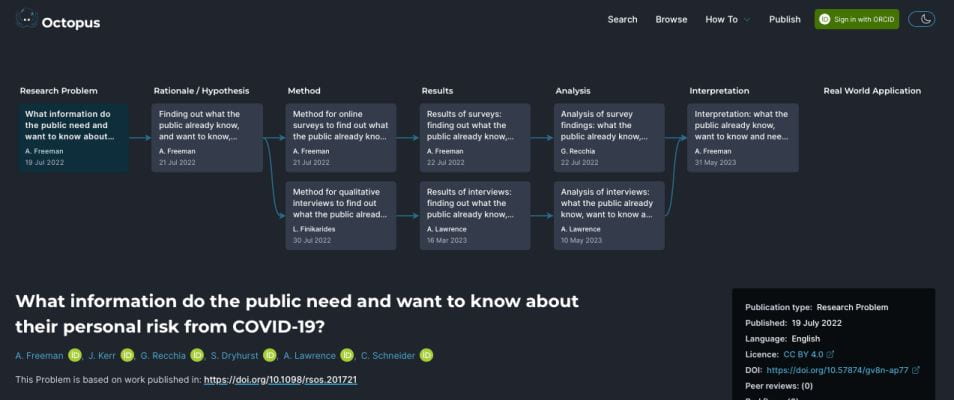

Octopus.ac launched almost a year ago, slightly quietly because we wanted to add features and smooth out wrinkles with our user groups before we were fully ready for the world. Now we’re coming to crunch point: we need early adopters to start using it. Because every publication in Octopus is linked to another, we ‘pre-seeded’ Octopus with research topics and problems to act as a kind of skeleton on which the living coral reef of publications can grow – but we need researchers’ help now to start publishing ‘real’ work on the platform.

As I talk to researchers about it, I find there are often three main reasons for hesitation. I hope that here I can address each one:

Why would I want to publish in Octopus?

Of course you want to publish on Octopus because you support its broader aspirations to change the incentive structure and improve the research culture and excellence. Even the keenest reformer, however, can’t spend time trying every new innovation without any tangible benefits. So, what can Octopus do for you?

Well, everything you publish on Octopus gets its own doi immediately, and appears on your public profile: ideal for showing potential employers everything you have done. Octopus also has a pipeline built in so that everything can go automatically into your institution’s repository. There it will be counted towards their reporting – on work that’s done at the institution, and on work that’s Open Access. That means that they will be happy with you for using it.

On top of those, Octopus allows a couple of other useful features. One is getting reviews – and (soon) quality metrics – on your work. Compared with reviews on a whole ‘paper’, reviews and ratings on Octopus publications can be much more meaningful and specific because they are only about, say, your analysis or your protocol. They can also be much more constructive: if you’ve published a theory, and you later want to build on that with some experimental work, having feedback on the theory before you do so is much more useful than afterwards!

Won’t people steal my ideas if I publish them on Octopus?

When Charles Darwin first started thinking about, and writing about, his ideas of how evolution might happen by means of natural selection, he kept them to himself and his close friends. For about 20 years. He wanted to collect data and publish everything in one book.

When he received a letter from the young Alfred Russell Wallace outlining the same ideas, he was distraught. Writing to his close friend Charles Lyell, Darwin says “Your words have come true with a vengeance that I should be forestalled… So all my originality, whatever it may amount to, will be smashed.” Darwin was very lucky to have good friends who could arrange that both his and Wallace’s ideas were published together in a joint paper with the Linnean Society of London.

Today, rather than needing friends in high places who can get you out of such trouble, you have Octopus. Don’t do a Darwin – put your ideas on Octopus as soon as you have formed them properly, so that they are date-stamped and assert your priority. If your ideas turn out to be good ones, they will forever be ‘yours’.

What do I link my work to in Octopus’ structure?

In Octopus, every publication has to be linked to an existing one. This is to ensure the maximum usefulness of everything that’s shared: experimental results can’t be shared without being linked to the relevant protocol etc; and over time all related work should end up clustered and linked together, making it easier to find.

However, that means that now, as Octopus starts up, it is a bit trickier to find a closely related piece of work to act as an anchor for your own. We have, though, created research topics, so that you should be able to find something relevant to act as an anchor, even if it is not as specific as you might like.

You could, in fact, help Octopus – as well as getting additional publication credit yourself – by writing and publishing higher-level research problems. Each research problem publication is only a couple of paragraphs long, and just needs to outline a research question (such as ‘how can we reduce mortality from breast cancer?’) which acknowledges the history of the problem. It doesn’t need to go into a literature review of work that has tried to address that problem: that is the job of the next publication down in the chain, the ‘theoretical rationale/hypothesis’.

The more people publish these small, relatively easy-to-create publications, the easier the whole system will become for others to use.

If you want to try out Octopus, do your bit for improving the research culture and publication system, and get yourself some credit on your CV and with your institution, then put aside a lunchbreak. Try writing a few paragraphs to outline a research problem that you are familiar with, log in to Octopus.ac, and publish it, attached to the most relevant publication or research topic that you can find. Maybe even make it a social event – like a Wikipedia hackathon – and get a few friends together to publish a raft of research problems. Remember, each one will appear on your CV, so you’ll be gaining personal credit whilst also helping out the greater good.